There’s a specific moment from 1991 that I remember standing in my friend’s bedroom, watching a brown and beige computer boot up. I’d been using an Acorn Electron until then—a purely beige, smaller version of the BBC Micro that ended up in schools across the UK. It was fine for basic programming and simple games.

But this was the Commodore 64 (C64 to its friends). It had bigger memory, faster processing, better graphics, and superior sound capabilities—features, features, features.

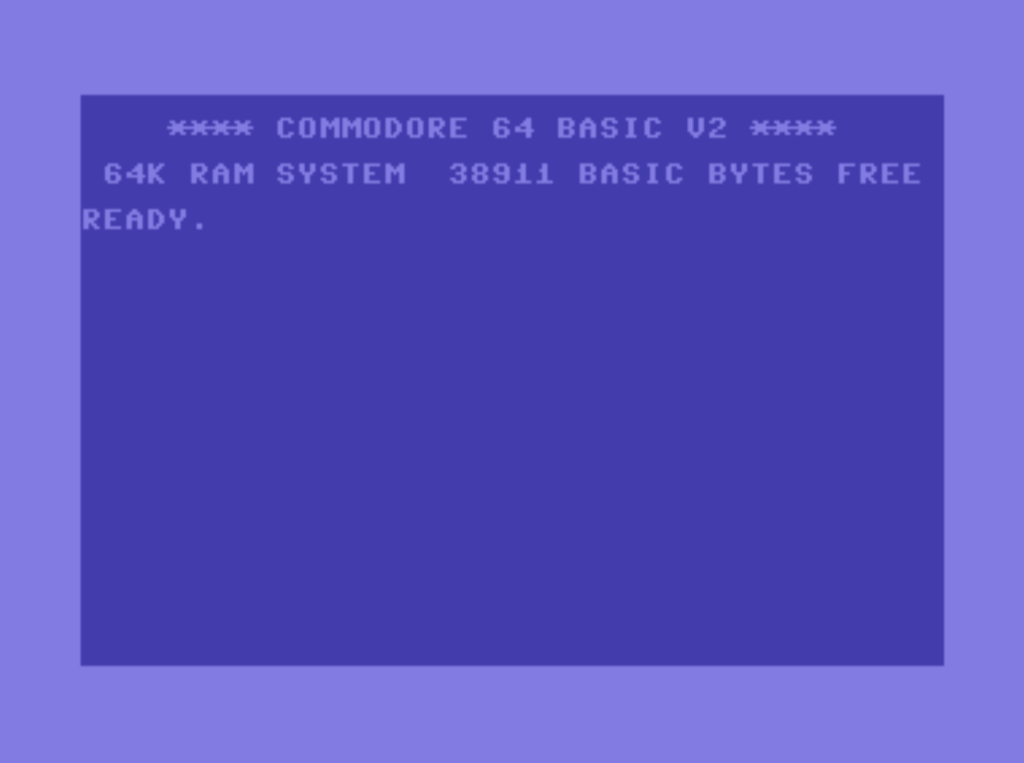

It wasn’t just the technical improvement, but the sense of possibility. Watching that familiar blue screen appear with its cheerful “READY” prompt and flashing cursor, I felt a little world opening up.

Sixty-four thousand bytes of memory (an empty Word doc created in this year of our Lord 2025 is 16k for reference), and somehow, it contained infinite potential. This was before we knew that constraints were supposed to limit us.

Delayed gratification

The ritual began with the tape deck. You’d slide and click in a cassette—maybe Elite, maybe The Last Ninja—press play, and wait—five minutes, ten minutes, sometimes longer.

The loading screen would flicker with abstract patterns while synthesised music played, compositions created explicitly for this interstitial moment. Rob Hubbard’s loading themes were as eagerly anticipated as the games themselves.

(Sometimes there might even be a simple game to play while waiting. Truly juice was set to max.)

Modern sensibilities would call this inefficient, primitive, and a barrier to immediate gratification that needed solving. But there was something magnificent about that forced patience.

The anticipation built. You committed to your choice. When the game finally loaded, you played it correctly, completely, because loading something else meant another ten-minute investment.

Sharing is caring

The physical nature of sharing created a genuine community. We’d swap cassettes and cartridges like trading cards, moving through our social networks with recommendations and discoveries.

“You have to try this.” “Wait until you see what happens in level three.” The constraint of physical media meant every game was a deliberate acquisition, every recommendation carried weight.

This was constraint creating value, not limiting it.

Constrained genius

Consider Paradroid, Andrew Braybrook‘s 1985 masterpiece. He created a complete universe in 64k of memory—less storage than a single high-resolution photograph today. The massive spaceship has dozens of robot types, each with distinct behaviours and abilities.

A strategic puzzle game wrapped in arcade action. Atmospheric sound design that made empty corridors feel ominous.

The magic wasn’t despite the constraints. It was because of them.

Every byte mattered, every sprite had to earn its place, and every sound effect was crafted with obsessive precision because there was no room for waste. The limitation forced focus, and focus created brilliance. Braybrook couldn’t add unnecessary features or bloated interfaces. He had to solve the core challenge: creating compelling depth within absolute restrictions.

The answer was precision in execution and crystal clarity in vision.

We’ve forgotten this discipline mainly. Modern development operates under the assumption that more is better—more features, options, power, and storage. The iPhone in your pocket has roughly 100,000 times the memory of that Commodore 64, yet somehow, we struggle to create experiences that feel as focused or magical.

This isn’t just nostalgia speaking. It recognises a fundamental truth: unlimited resources don’t automatically create better outcomes. They often develop worse ones. When you can do anything, you lose the discipline of doing specific things extraordinarily well.

The most successful products and campaigns today succeed not because they do everything, but because they do particular things with obsessive precision. They choose constraints deliberately and work brilliantly within them. The best mobile apps feel like Paradroid—complete worlds within defined boundaries, every element serving a purpose.

Here endeth the lesson

The lesson isn’t that we should return to 64k of memory or five-minute loading times. Constraint remains one of the most potent creative forces available to us. When you define clear boundaries—budget, timeline, scope, audience—you force focused thinking that produces extraordinary results.

The 64k universe taught us that limitations don’t shrink possibilities. They concentrate them. And sometimes, concentration creates magic that unlimited resources never could.

Next time you face constraints, remember that brown and beige computer. Somewhere in those restrictions lies your Paradroid—the brilliant solution that could only exist within those specific boundaries.

You just need to find it.

This article was written with the assistance of AI.