Picture the typical airline advertisement in 1962: a stewardess serving cocktails (back when that was somehow peak sophistication), promises of “friendly skies,” and copy that treated readers like they’d never seen an aeroplane-or possibly any form of transport more complex than a particularly ambitious donkey.

Now imagine you’re the kind of person who reads The New Yorker. You know—educated, well-travelled, probably owns at least three books that aren’t about business strategy, and possesses the sort of refined cynicism that can spot a manipulative sales pitch from roughly the same distance a badger can detect an unguarded garden shed. (And honestly, have you ever tried to fool a badger? They’re having none of it.)

That airline ad isn’t just ineffective for this audience—it’s actively insulting, like serving instant coffee to someone who grinds their beans while humming Vivaldi.

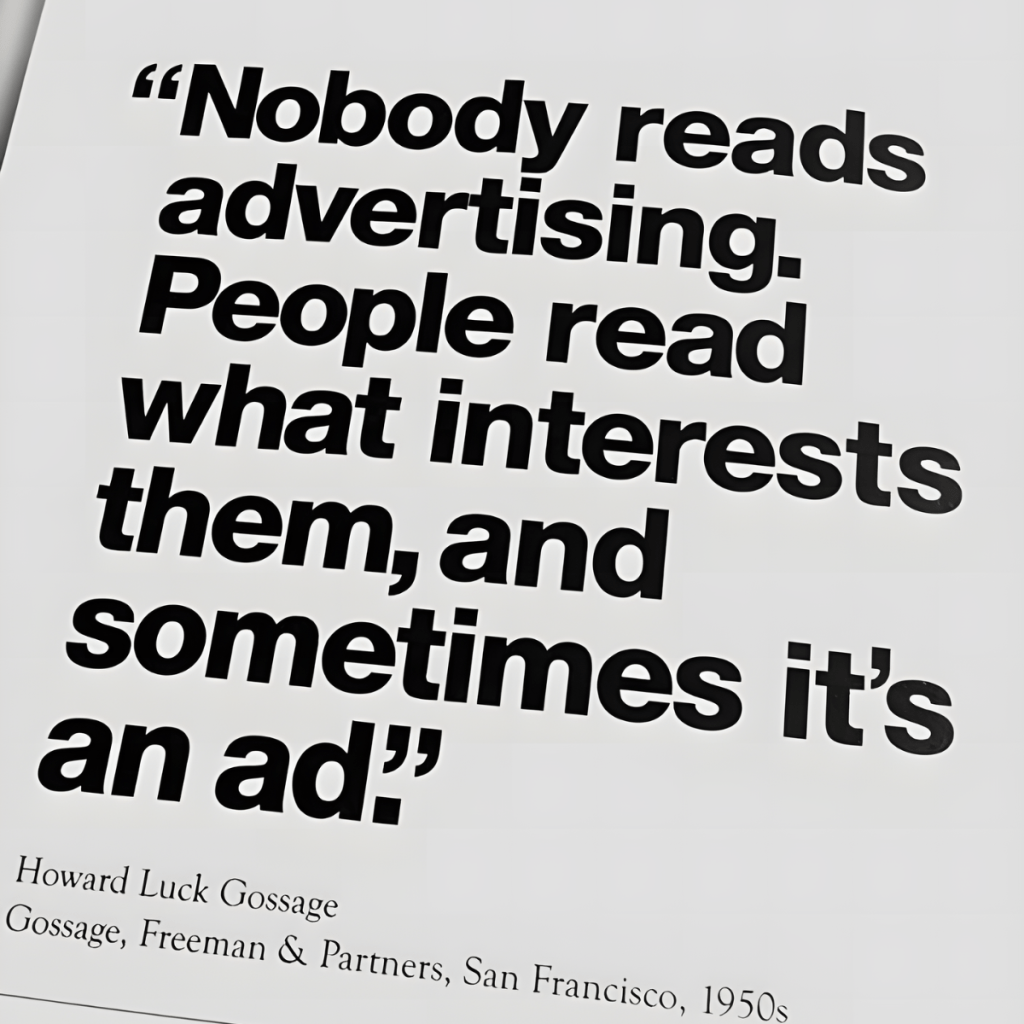

Howard Gossage saw this disconnect and thought, “Right, this is properly dumb.” Then he built his entire agency around fixing it.

The species study that changed everything

While Madison Avenue was perfecting the art of shouting louder (because surely volume equals persuasion?), Gossage was quietly studying an entirely different consumer species. Think of him as a marketing anthropologist who’d stumbled upon a tribe everyone knew existed but nobody could communicate with.

This tribe—let’s call them the Intellectual Sophisticates—read quality magazines, attended gallery openings, and viewed most advertising as cultural pollution roughly equivalent to someone playing the kazoo during a string quartet. (Not that there’s anything wrong with kazoos, mind you. They have their place. That place is just nowhere near Brahms.)

Gossage realised these weren’t difficult customers. They were underserved customers. It was like discovering a group of people who desperately wanted good coffee, but everyone kept offering them tea made with lukewarm water and a Pot Noodle.

Speaking fluent sophisticate (without sounding like a pretentious turnip)

Here’s where Gossage got properly clever. Instead of dumbing down his message for the masses, he smartened everything up for the minority. Not in a show-offy, “look how clever I am” way—more like an excellent teacher who makes quantum physics sound like common sense over a pint.

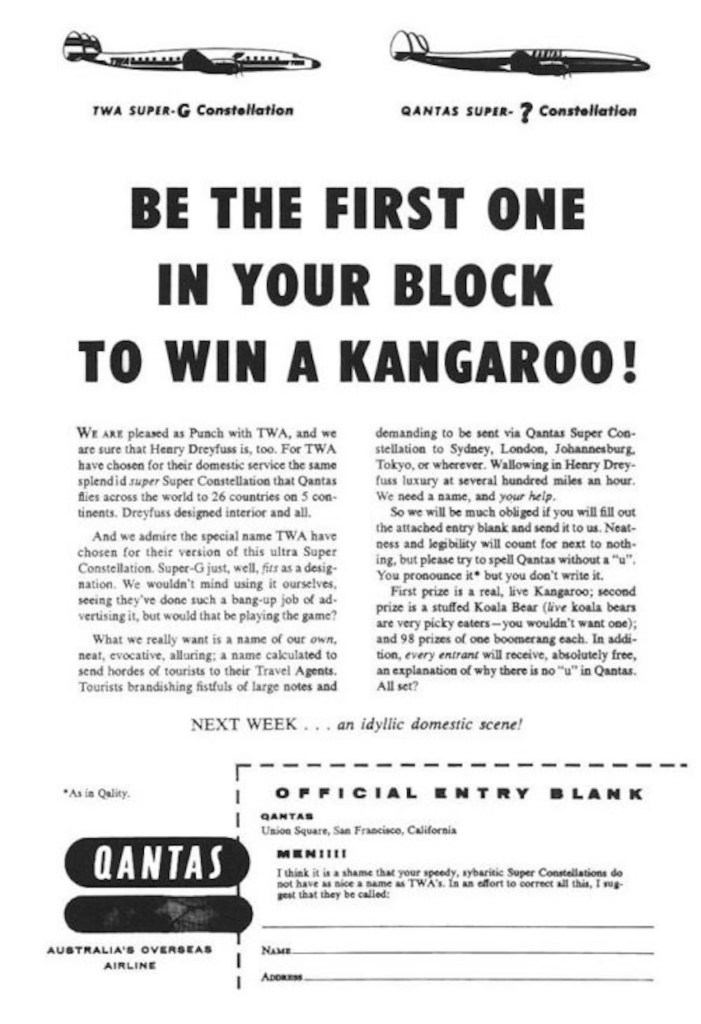

Qantas and the great kangaroo census

When Qantas wanted American customers, the obvious approach was safety, service, or exotic destinations—the usual travel brochure nonsense that makes everywhere sound like a holiday camp run by particularly enthusiastic geography teachers.

Gossage instead created an advertisement that read like a charming domestic dispute: he and his wife couldn’t agree on whether Australia had more kangaroos than people. Would readers help settle this burning question by requesting a fact sheet?

Brilliant, right? He’d turned market research into intellectual curiosity. New Yorker readers didn’t just want to book flights—they tried to solve puzzles, demonstrate their worldliness, and feel like they were participating in something cleverer than “Buy This Thing Because Reasons.”

The campaign succeeded because it made engagement feel like joining a sophisticated dinner party conversation rather than responding to someone shouting through a megaphone in the high street.

Irish coffee and the art of cultural translation

For Irish coffee, Gossage didn’t just promote a drink—he positioned it as a cultural artefact worthy of sophisticated appreciation. His advertisements read like restaurant reviews written by someone who cared about provenance and story, not just “tastes nice, please buy.”

He treated the drink like a museum curator would treat a newly discovered Picasso sketch.

The target audience devoured this approach. (Metaphorically. Though probably literally too, given it involved alcohol.) Here was advertising that made them feel more worldly because they knew the backstory of their cocktail.

Ordering Irish coffee became less about wanting a warm drink and more about demonstrating cultural literacy, like knowing the difference between Handel and Haydn at a dinner party.

Sierra Club and environmental arguments for people who read books

When the Sierra Club needed to stop a proposed dam in the Grand Canyon, Gossage didn’t create emotional appeals about natural beauty. That would have been the obvious route—sweeping landscape photos, soaring music, maybe a voiceover by someone with the voice typically reserved for nature documentaries and luxury car adverts.

Instead, he crafted full-page newspaper advertisements that read like reasoned essays—proper arguments with evidence and everything. The headline “Should we also flood the Sistine Chapel so tourists can get nearer the ceiling?” became famous not because it was catchy, but because it gave the educated class a framework for understanding environmental issues that didn’t make them feel like someone with a clipboard and an alarming amount of enthusiasm was lecturing them.

Gossage had provided them with intellectual ammunition for dinner party conversations.

(Because nothing says sophisticated discourse quite like being able to reference both Michelangelo and dam construction in the same sentence.)

The aha! moment: Premium access to premium minds

Here’s what Gossage understood that completely escaped his contemporaries—and still escapes most marketers today, if we’re honest: the educated consumer wasn’t anti-advertising. They were anti-stupid advertising.

Show them advertising that demonstrated cultural fluency, historical knowledge, or aesthetic sophistication, and they didn’t just tolerate it—they collected it, filed it away. Discussed it at dinner parties. Became advocates for the product and the revolutionary idea that this brand actually “got it.”

This wasn’t about conversation versus monologue, as marketing textbooks sometimes suggest.

(Though fair, most marketing textbooks make watching paint dry seem like an extreme sport.)

This was about access. Gossage had discovered the secret password to social circles that had previously been about as permeable to commercial messages as a particularly stubborn jar of pickles.

He didn’t just create advertisements—he created cultural credentials—membership cards to an intellectual elite—the marketing equivalent of knowing which fork to use for the fish course.

The business model behind the philosophy (because someone has to pay for all this cleverness)

Gossage’s approach makes perfect commercial sense once you understand his true insight. There was an entirely underserved market of influential consumers actively seeking brands that reflected their values and intelligence level.

These consumers didn’t want cheaper products or more convenient services—they wanted brands that made them feel sophisticated for choosing them, like the difference between shopping at a supermarket and at a farmer’s market where the stallholder knows the life story of every carrot.

They were willing to pay premium prices for this feeling. They needed someone to speak their language first, rather than shouting at them in gibberish marketing.

Gossage essentially created the template for what we now call “premium positioning,” but he used cultural intelligence instead of using price or exclusivity as the differentiator. His advertisements were the marketing equivalent of a secret handshake.

What modern brands miss

Today’s equivalent of Gossage’s audience probably listens to podcasts that make them feel smarter, reads articles that don’t insult their intelligence, and shops at places that feel curated rather than algorithmically optimised for maximum efficiency and minimum soul.

Yet most brands still approach them with the digital equivalent of 1960s hard-sell techniques: retargeting ads that follow them around the internet like an overly persistent salesperson, discount codes that scream “PLEASE BUY SOMETHING, ANYTHING,” and social proof notifications that essentially say “Other people bought this, so you should too, like some sort of commercial sheep.”

(It’s like having incredibly sophisticated targeting technology and using it to deliver increasingly refined versions of “HELLO THERE, WOULD YOU LIKE TO BUY A THING?”)

The brands that succeed with this audience today—Patagonia‘s environmental storytelling, Airbnb‘s early positioning as cultural discovery rather than cheaper hotels, anything that manages to be associated with TED Talks without making you want to hide under a desk—are essentially following the Gossage playbook without realising it.

They’re providing cultural credentials along with commercial products. Making their customers feel interested in choosing them.

The Gossage standard today

If Gossage were operating today, he’d probably be fascinated by digital advertising’s targeting capabilities—the ability to reach New Yorker subscribers directly rather than hoping they’d stumble across his print ads while browsing for something completely different.

But he’d be horrified by how most brands waste this precision. Instead of using sophisticated targeting to deliver sophisticated messages, most brands use it to provide the same generic appeals more efficiently. It’s like having a precision instrument and using it as a very expensive hammer.

They’ve solved the wrong problem entirely.

The real opportunity—then and now—isn’t reaching more people. It’s reaching the right people in a way that makes them feel understood rather than hunted by an algorithm with commitment issues.

The elegant solution (that’s still sitting there, waiting)

Gossage proved that if you can demonstrate genuine cultural fluency, educated consumers will not only tolerate your commercial message but amplify it. They’ll become unpaid advocates for your brand because engaging with it makes them more interested.

In a world where everyone is fighting for attention like seagulls around a dropped ice cream, this remains the most elegant solution: don’t demand attention; earn advocacy.

The educated audience is still there, still influential, still underserved by advertising that treats intelligence as a barrier rather than an opportunity.

(Like having a conversation with someone brilliant and spending the entire time talking very slowly and loudly, just in case.)

The question isn’t whether Howard Gossage’s insights still apply. The question is whether anyone is still smart enough—and brave enough—to apply them.

Because here’s the thing: it’s much easier to shout at everyone than to converse with someone. But guess which one changes minds?

This article was written with the assistance of AI.